A Democrat's Journey: John De Coninck

Plantain proudly presents this beloved book for John De Coninck, our co-founder's kin and a fervent advocate for democracy, social justice, and activism.

His self-penned memoir traverses his life from Brussels to the Congo and back as a child, and then onwards to the United Kingdom, Uganda and other African countries. It encapsulates a rich life dedicated to systemic social change.

Our expertise in editing and design brought his compelling narrative to life, ensuring every page resonates with his profound legacy.

“My first childhood memories connect to my father’s unusual theatrical adventures: in 1950, months after my birth, he bought an old barge with friends and transformed it into ‘Le Théâtre Flottant’ – ‘The Floating Theatre.’ This ship travelled up and down the rivers of Belgium and France, stopping at towns along the banks for a few days at a time. They performed, for local audiences, plays that this small band of idealistic young writers and actors had written.

In time, the theatre barge began towing another that now provided a living space for the group. Accommodation was necessarily cramped: my first memories were thus of spinach being drained by my mother into a tiny kitchen sink. There was also a playpen on the ship’s roof, where I would (at times reluctantly) share the square metre or so with Marianne, the daughter of another actor. Hence also a memory of a world constantly on the move: while the barge was slowly but surely pulled along this or that river, landscapes slowly unfolded as I played or quarrelled with Marianne in our pen.

Did this give me a later urge to travel and explore? Perhaps.”

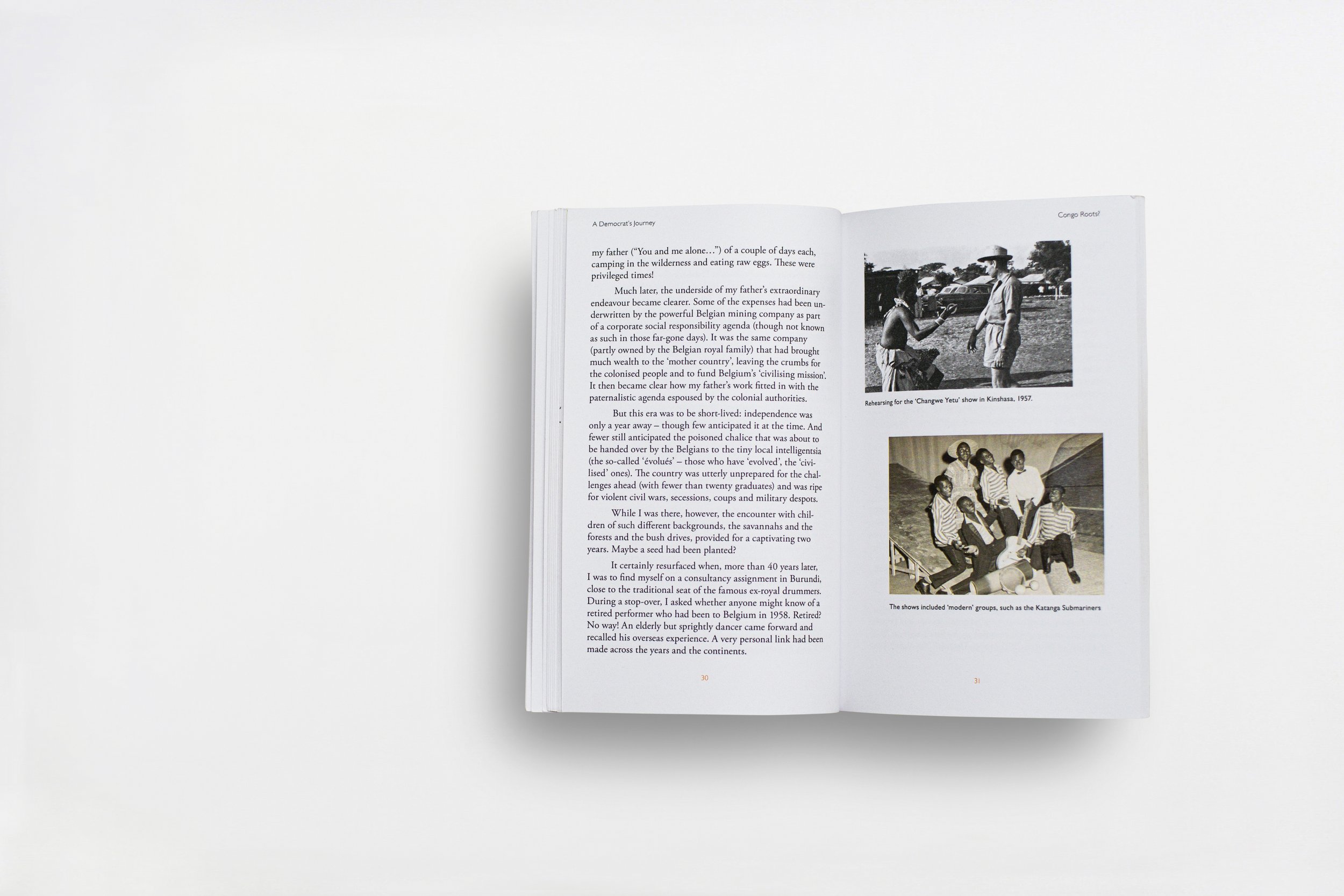

“Much later, the underside of my father’s extraordinary endeavour became clearer. Some of the expenses had been underwritten by the powerful Belgian mining company as part of a corporate social responsibility agenda (though not known as such in those far-gone days). It was the same company (partly owned by the Belgian royal family) that had brought much wealth to the ‘mother country’, leaving the crumbs for the colonised people and to fund Belgium’s ‘civilising mission’. It then became clear how my father’s work fitted in with the paternalistic agenda espoused by the colonial authorities.“

“The staff complement consisted of a disparate group of lecturers attracted to Juba for various reasons: experienced expatriate professors with a passion for the region, young Sudanese academics (including two teaching assistants I was to supervise) looking for a start to their career, as well as other staff who could find nowhere else to go. All lived on campus, some (like us) in modernised tin rondavels. Our little house was nevertheless much loved, though regularly infested by scorpions and snakes... The social life was inward-looking, much as it had been at Makerere. Still, long-term friendships, cemented by our experiences of living in a very challenging environment, were also created.”

“A new mode of life appeared in Kampala: most commuters walked back home (public transport no longer existed) in the early afternoon, and by 4 pm, the town was deserted. By 6, the nightly din of gunfire had started. A rare vehicle could be heard speeding, and occasional screams too. Appalling sweeps (‘panda gali’ – ‘get into the truck’ in Swahili) and the jailing of innocent people (many never to be seen again) became the hallmark of the regime in place. It fired popular resistance that eventually led to an armed insurrection commanded by a certain Yoweri Museveni.”