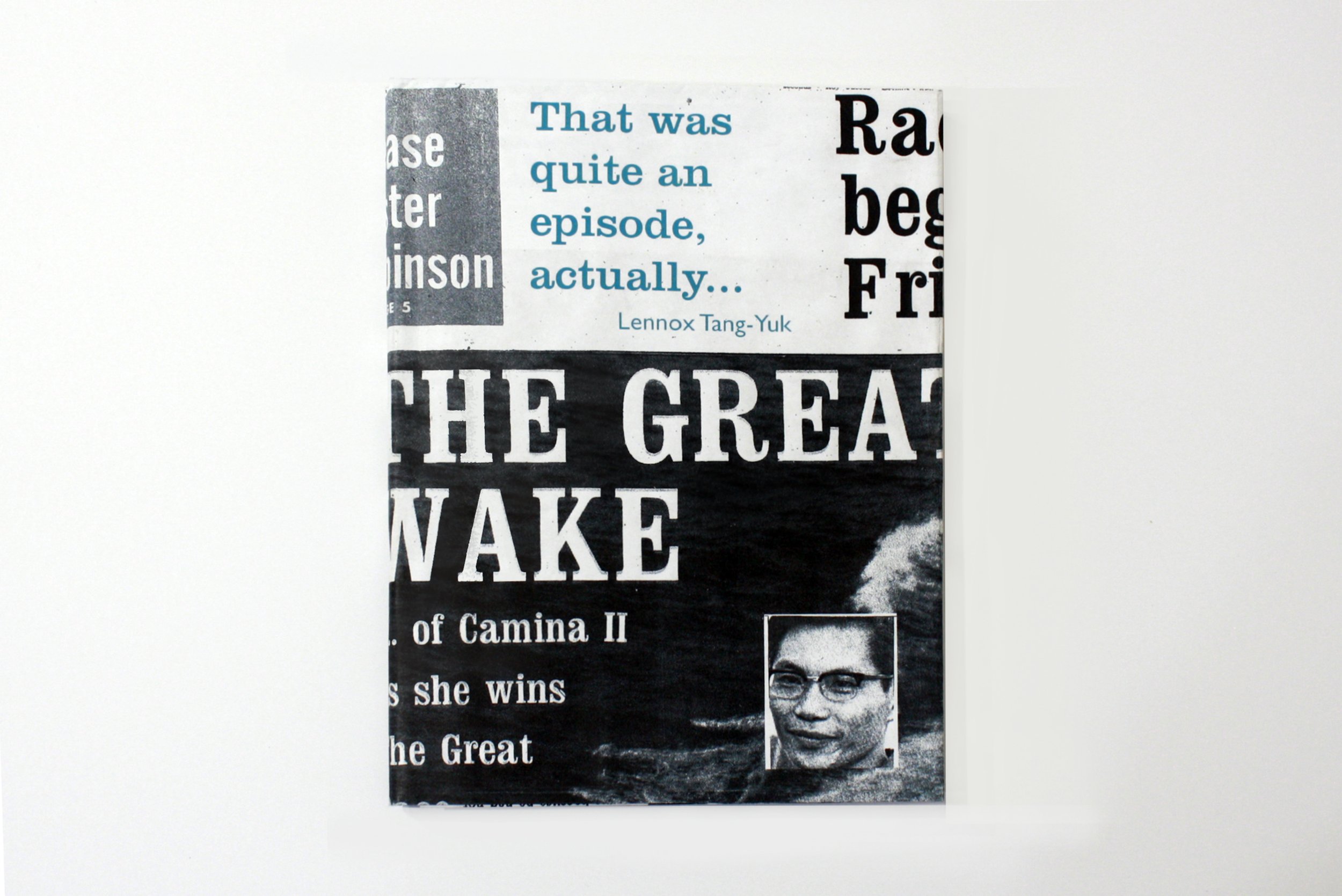

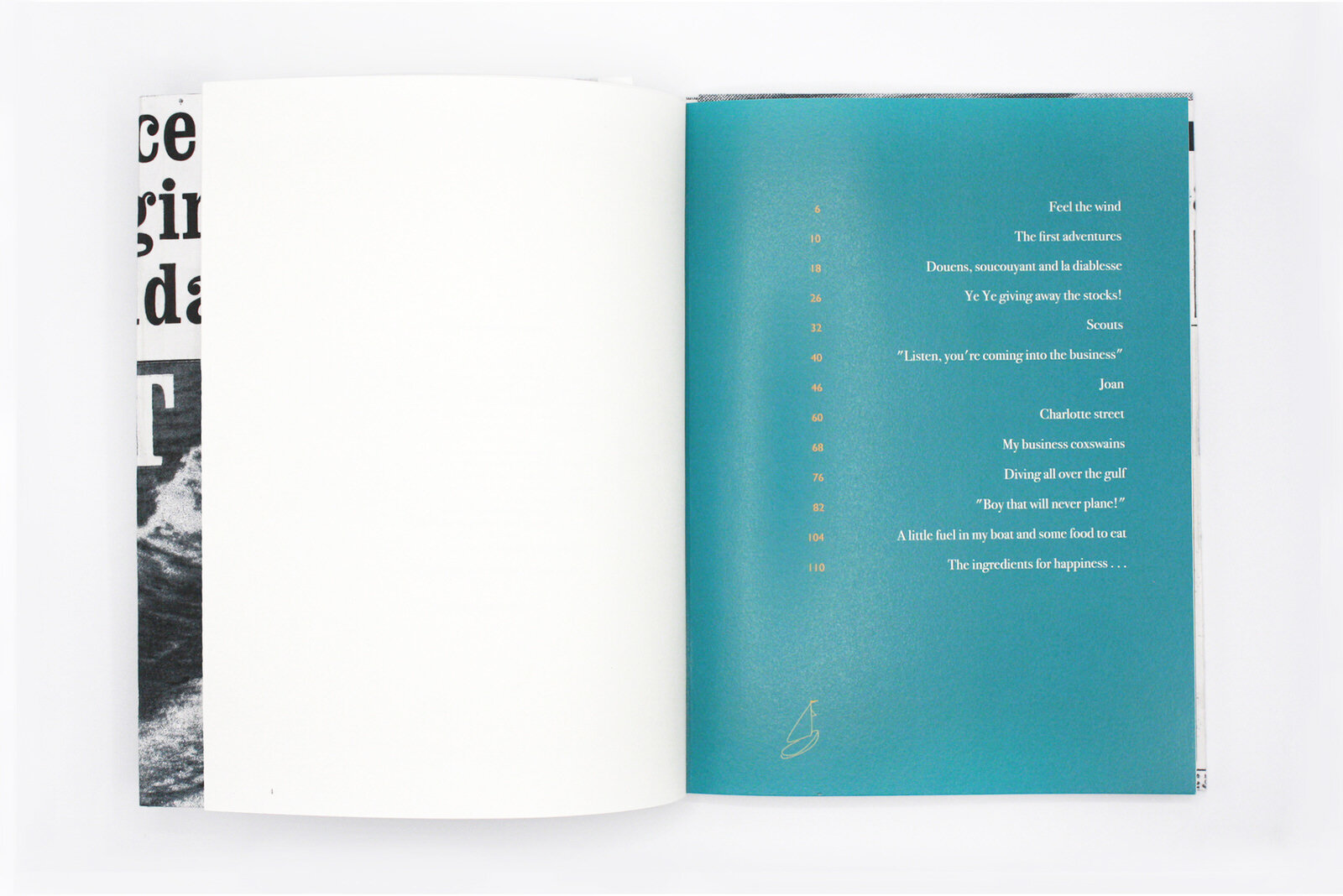

Lennox Tang Yuk: That Was Quite An Episode, Actually...

There is an aura of ease that surrounds Lennox.

As he recounted his outdoor adventures, and the decades of work he put into building one of the Caribbean’s most successful companies (that his children lead today), it was always with humility, candor and humor that he shared his stories.

His values were evident from the start of the project - integrity, kindness, curiosity - and we thank Lennox for letting us be a part of this episode in his life.

As you take a look at this project, consider that the book’s design - from the colors to the typeface and size - was inspired by one of Lennox’s truest loves: The Caribbean Sea.

“My father really enjoyed this experience and he is pleased with the result. The approach and the writing suits his personality and the honesty and unpretentiousness was a bit of a shocker!” — Robert Tang Yuk

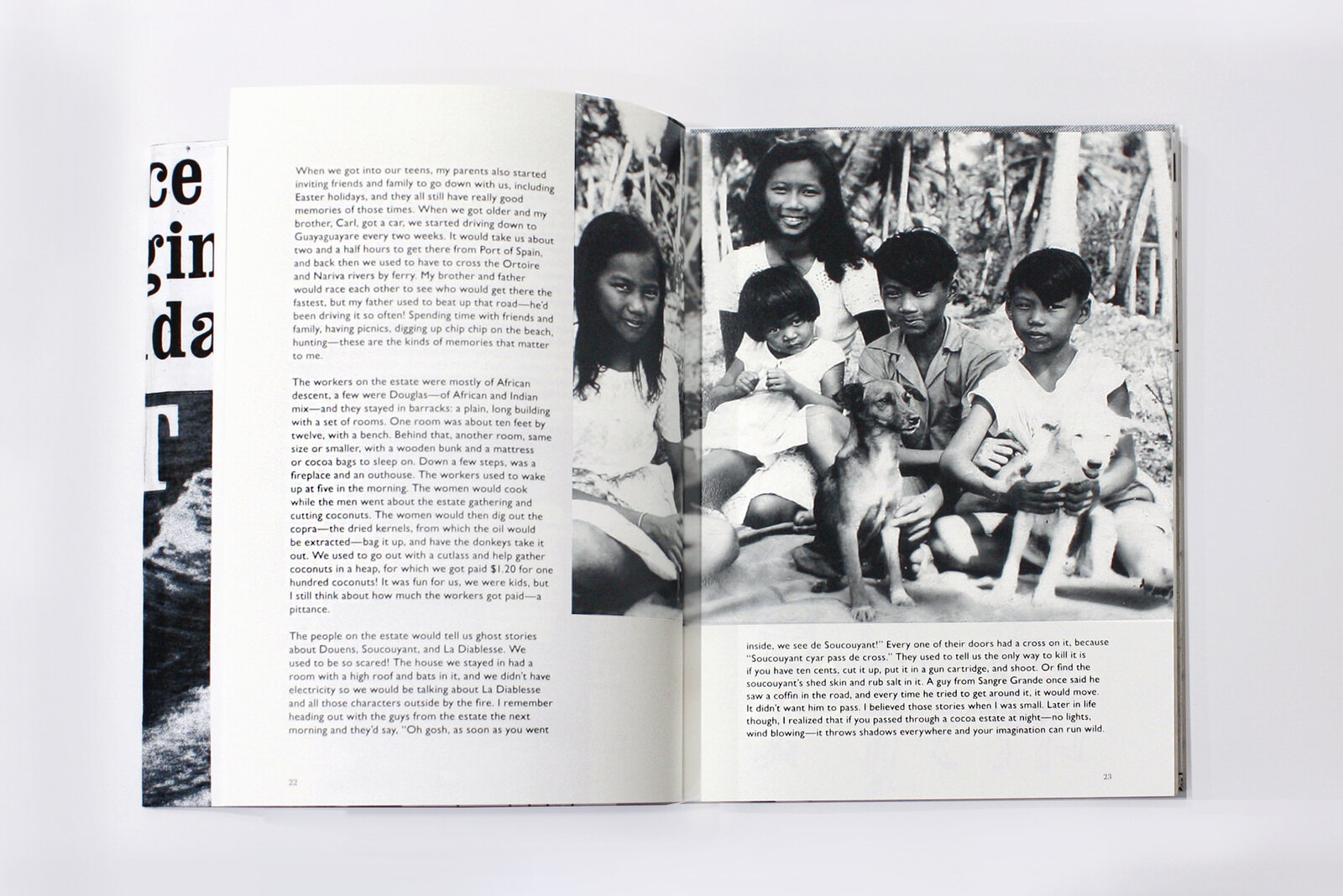

“The people on the estate would tell us ghost stories about Douens, Soucouyant, and La Diablesse. We used to be so scared! The house we stayed in had a room with a high roof and bats in it, and we didn’t have electricity so we would be talking about La Diablesse and all those characters outside by the fire. I remember heading out with the guys from the estate the next morning and they’d say, “Oh gosh, as soon as you went inside, we see de Soucouyant!” Every one of their doors had a cross on it, because “Soucouyant cyar pass de cross.” They used to tell us the only way to kill it is if you have ten cents, cut it up, put it in a gun cartridge, and shoot. Or find the soucouyant’s shed skin and rub salt in it. A guy from Sangre Grande once said he saw a coffin in the road, and every time he tried to get around it, it would move. It didn’t want him to pass. I believed those stories when I was small. Later in life though, I realized that if you passed through a cocoa estate at night—no lights, wind blowing—it throws shadows everywhere and your imagination can run wild.”

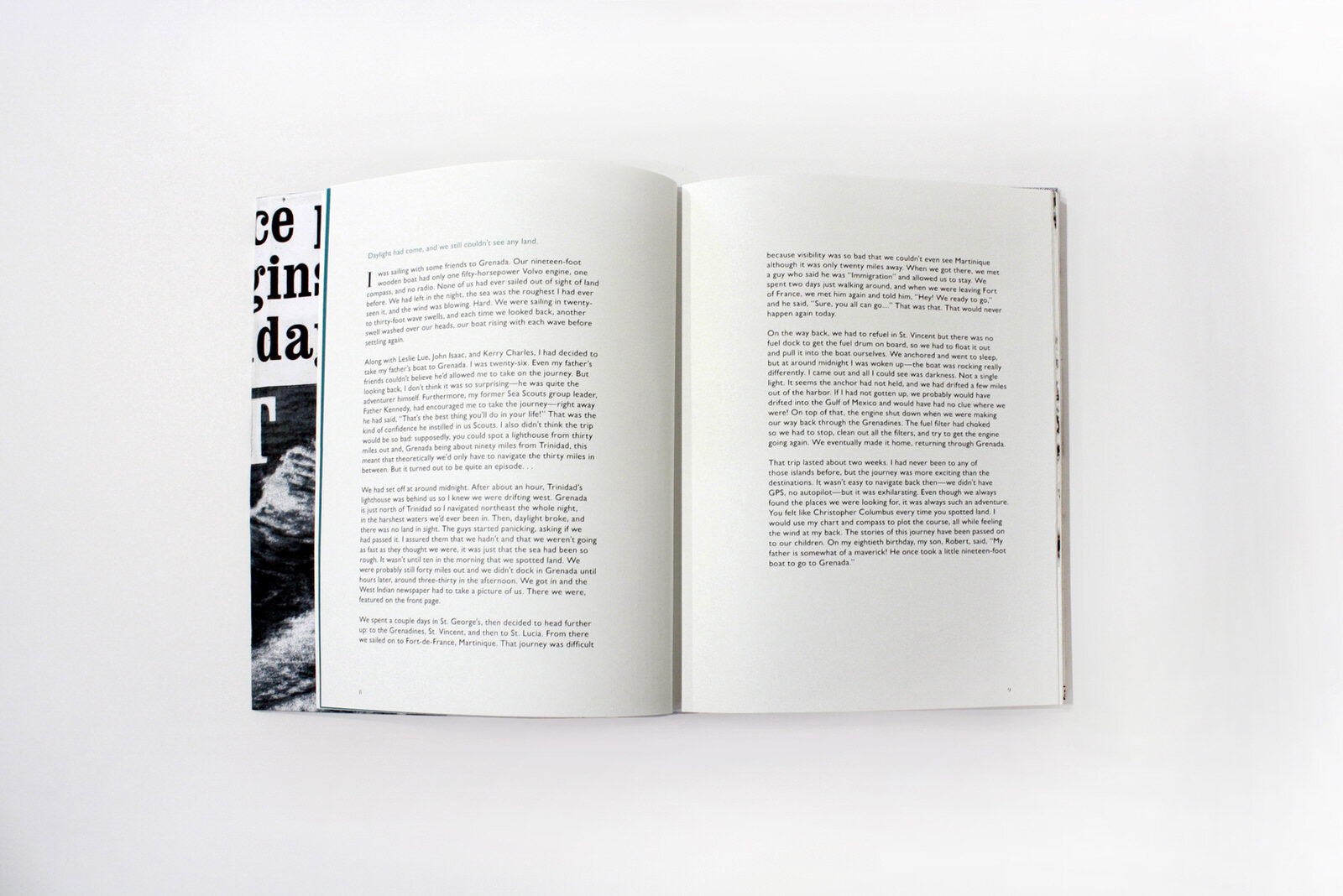

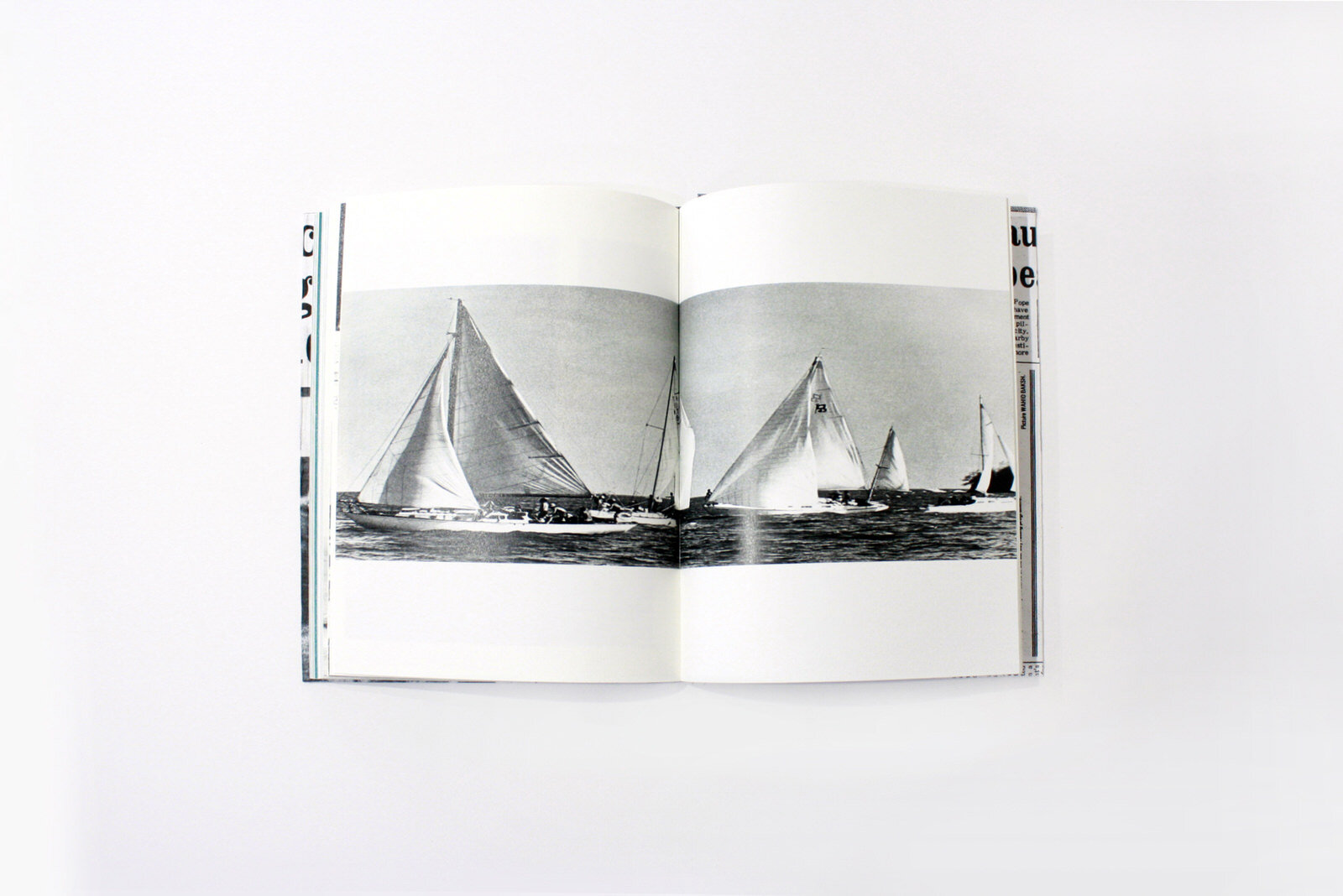

"Daylight had come, and we still couldn’t see any land.

I was sailing with some friends to Grenada. Our nineteen-foot wooden boat had only one fifty-horsepower Volvo engine, one compass, and no radio. None of us had ever sailed out of sight of land before. We had left in the night, the sea was the roughest I had ever seen it, and the wind was blowing. Hard. We were sailing in twenty- to thirty-foot wave swells, and each time we looked back, another swell washed over our heads, our boat rising with each wave before settling again.

Along with Leslie Lue, John Isaac, and Kerry Charles, I had decided to take my father’s boat to Grenada. I was twenty-six. Even my father’s friends couldn’t believe he’d allowed me to take on the journey. But looking back, I don’t think it was so surprising—he was quite the adventurer himself. Furthermore, my former Sea Scouts group leader, Father Kennedy, had encouraged me to take the journey—right away he had said, “That’s the best thing you’ll do in your life!” That was the kind of confidence he instilled in us Scouts. I also didn’t think the trip would be so bad: supposedly, you could spot a lighthouse from thirty miles out and, Grenada being about ninety miles from Trinidad, this meant that theoretically we'd only have to navigate the thirty miles in between. But it turned out to be quite an episode. . ."

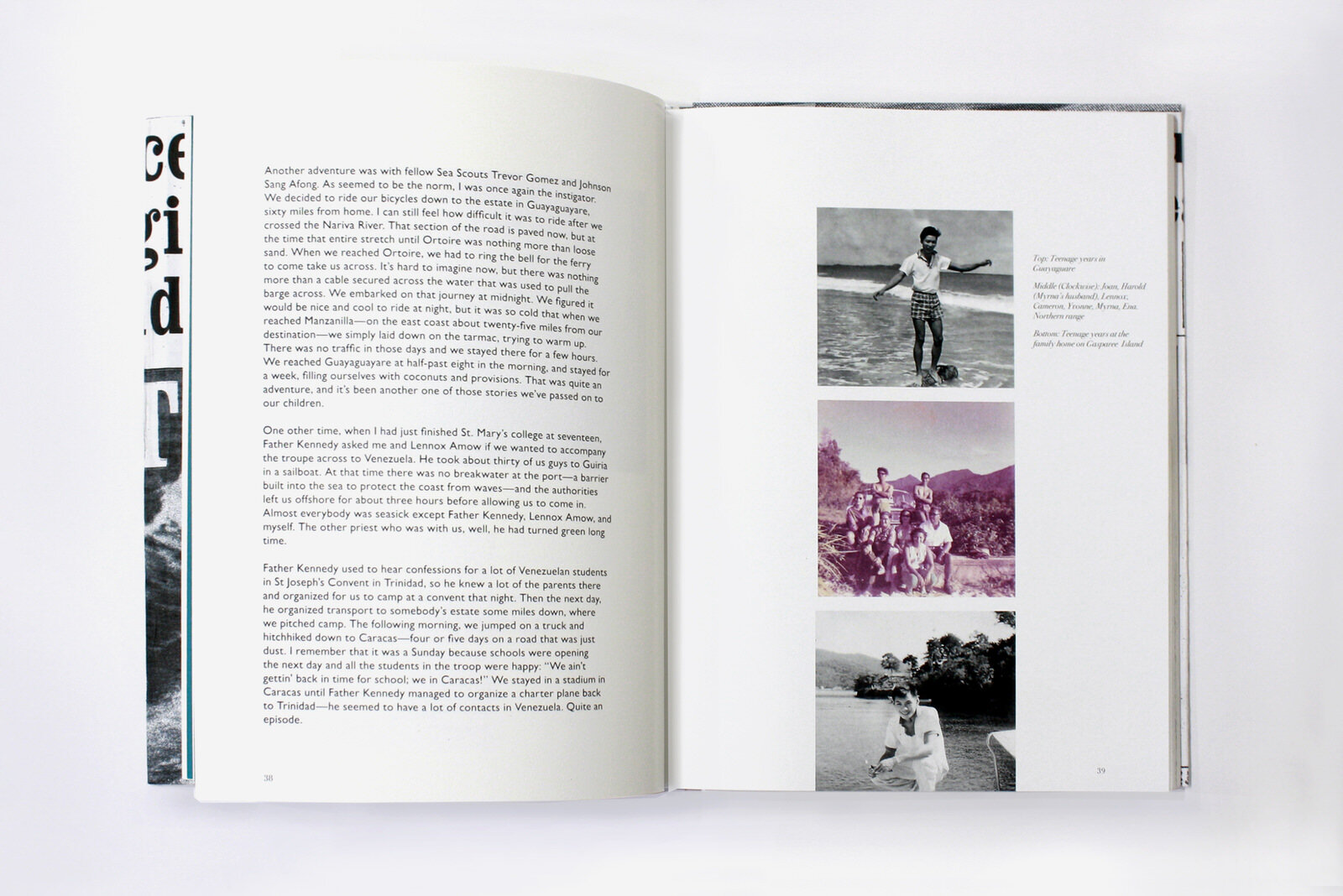

"Another adventure was with fellow Sea Scouts Trevor Gomez and Johnson Sang Afong. As seemed to be the norm, I was once again the instigator. We decided to ride our bicycles down to the estate in Guayaguayare, sixty miles from home. I can still feel how difficult it was to ride after we crossed the Nariva River. That section of the road is paved now, but at the time that entire stretch until Ortoire was nothing more than loose sand. When we reached Ortoire, we had to ring the bell for the ferry to come take us across. It’s hard to imagine now, but there was nothing more than a cable secured across the water that was used to pull the barge across. We embarked on that journey at midnight. We figured it would be nice and cool to ride at night, but it was so cold that when we reached Manzanilla—on the east coast about twenty-five miles from our destination—we simply laid down on the tarmac, trying to warm up. There was no traffic in those days and we stayed there for a few hours. We reached Guayaguayare at half-past eight in the morning, and stayed for a week, filling ourselves with coconuts and provisions. That was quite an adventure, and it’s been another one of those stories we’ve passed on to our children."

"It was in the 1960s that I started diving. My friends and I would go down to Gasparee Island on Saturdays, dive, shoot a couple of carite, and make it back in town by four o’clock for tennis. I then took up spearfishing and every weekend, for thirty to forty years, my friends and I would spend the days fishing all up and down the north coast, Toco, Guayaguayare, down in the Gulf, Tobago, and down de islands. The oceans have changed now, there aren't fish the way there used to be. I remember catching so much that I had enough to feed the children, and I can still see them racing lobsters in the yard whenever I got a big catch.

My friends and I shared some great times. During holidays, we’d pack the car with a boat engine, fishing and diving gear, and head out without knowing exactly where we’d be going. When we got to where we got to, we would rent a boat and head out. I think about those times and I wonder if young people do that, still, today."

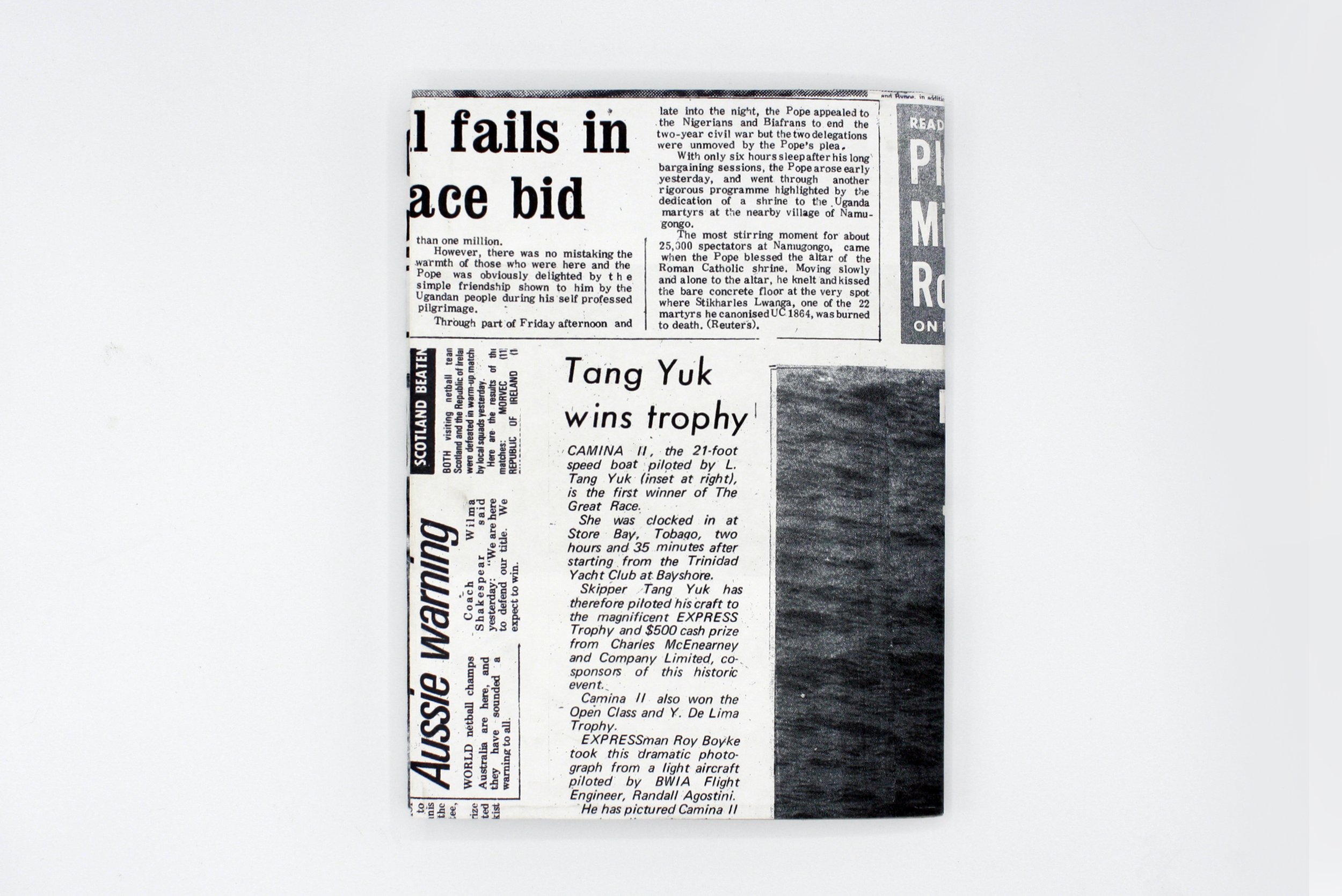

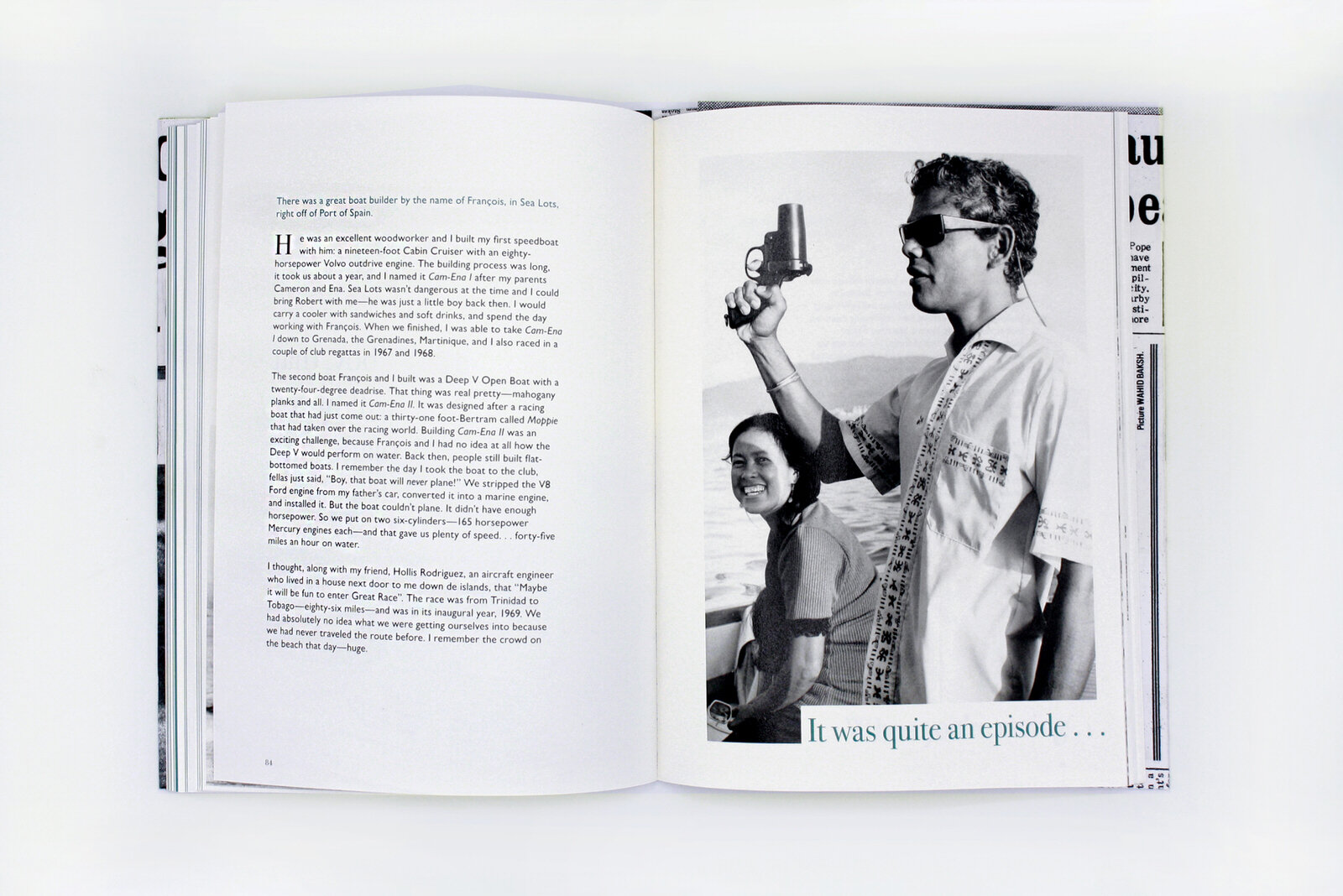

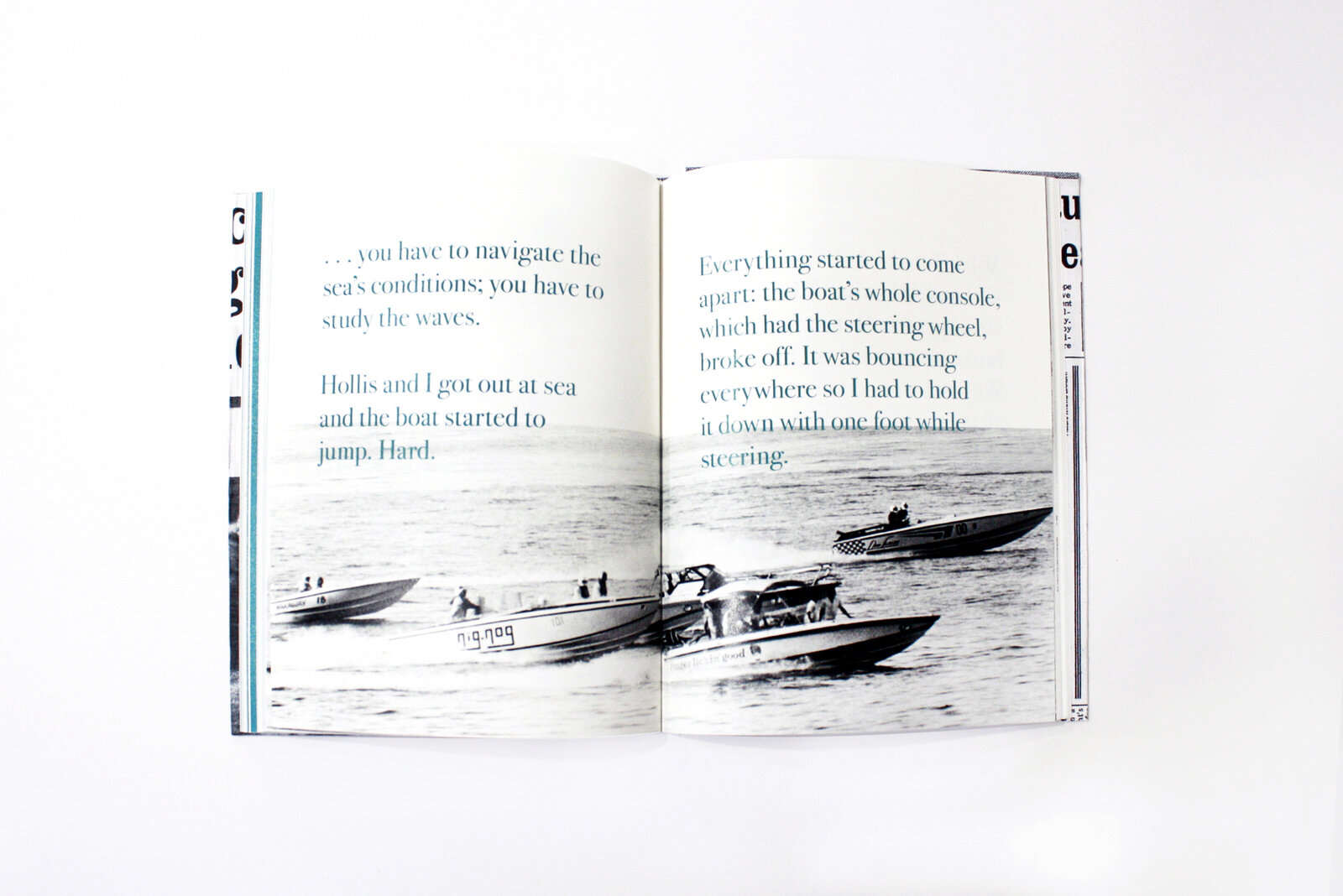

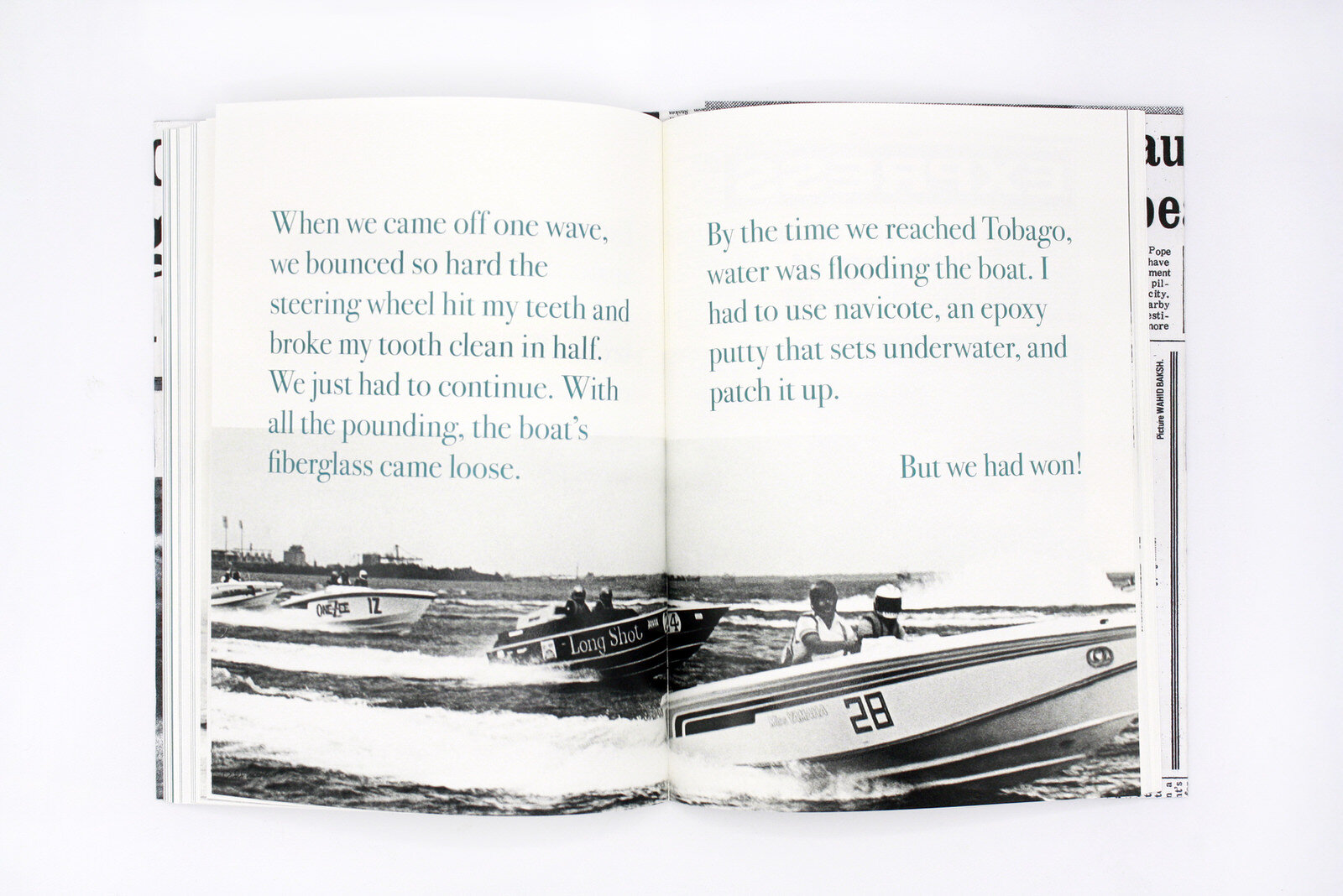

“I thought, along with my friend, Hollis Rodriguez, an aircraft engineer who lived in a house next door to me down de islands, that “Maybe it will be fun to enter Great Race”. The race was from Trinidad to Tobago—eighty-six miles—and was in its inaugural year, 1969. We had absolutely no idea what we were getting ourselves into because we had never traveled the route before. I remember the crowd on the beach that day—huge.”

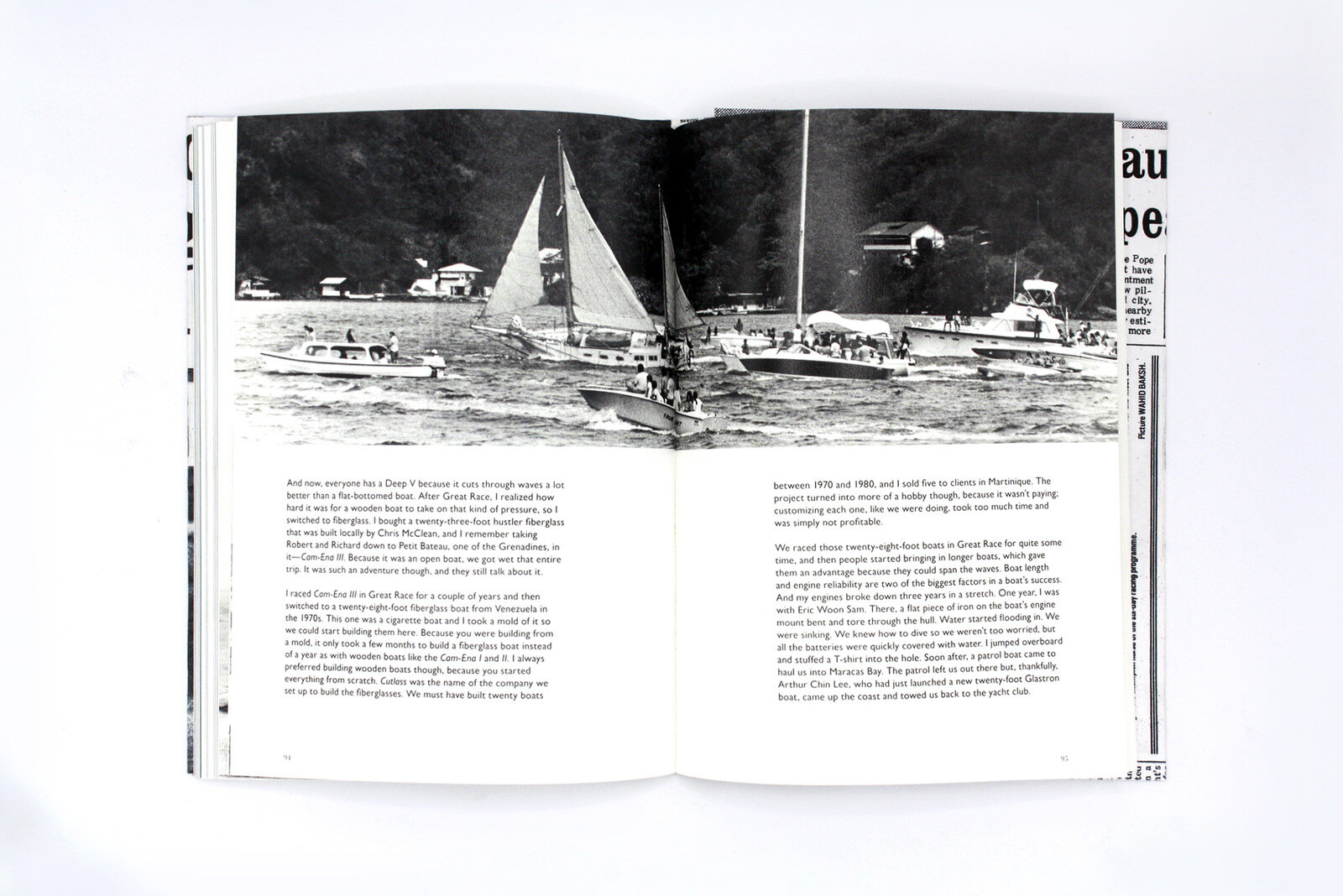

"I raced Cam-Ena III in Great Race for a couple of years and then switched to a twenty-eight-foot fiberglass boat from Venezuela in the 1970s. This one was a cigarette boat and I took a mold of it so we could start building them here. Because you were building from a mold, it only took a few months to build a fiberglass boat instead of a year as with wooden boats like the Cam-Ena I and II. I always preferred building wooden boats though, because you started everything from scratch. Cutlass was the name of the company we set up to build the fiberglasses. We must have built twenty boats between 1970 and 1980, and I sold five to clients in Martinique. The project turned into more of a hobby though, because it wasn’t paying; customizing each one, like we were doing, took too much time and was simply not profitable."

"The thing is special because of the way it runs and the way it is designed. It has the exact power-to-weight ratio that is required for a good speed. I can get up to Grenada in three and a half hours, rather than the six or seven hours it took before. I can go up to the Grenadines and stay up there for ten days without refueling, which saves me a lot, especially because fuel is expensive up there.

It was a significant purchase because I have always been frugal. I don’t lead an extravagant life. As long as I have a little bit of fuel, some food to eat and I can travel, I’m good. I prefer to invest in experiences. I see some of my kids spend $65-$75 on a steak—I don’t find that a useful investment. I could eat a $30 steak just fine. I have an old-school mentality; things didn’t come easy to me."